“We have a big responsibility to these horses,” Dale Romans explains. He’s not inclined to argue with people who hate horseracing, but Romans, who has been training Thoroughbreds for more than 35 years, isn’t about to apologize for what he does, either.

“I’d like people to know that the health of the horse comes first. We’re all out here doing this because we love the animals. It’s too hard work for too little money if you don’t.”

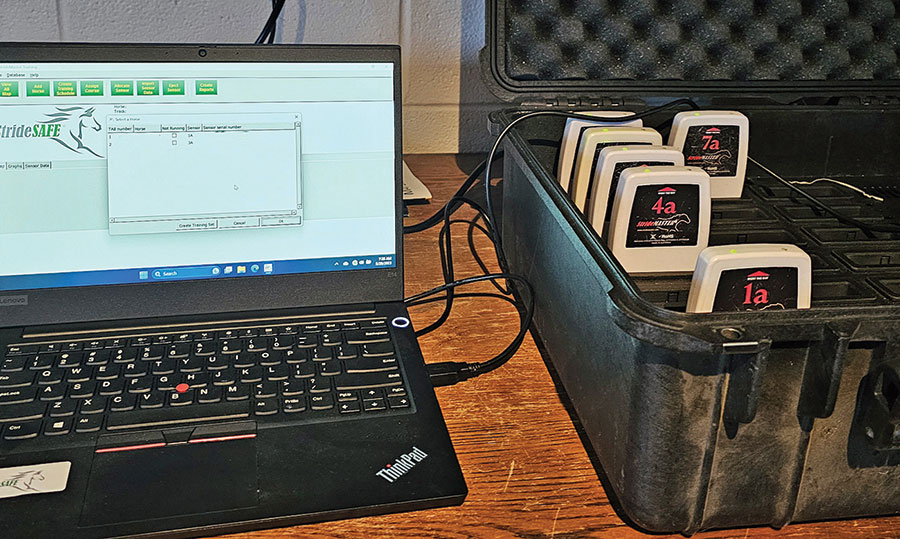

Romans’ focus on the health of his horses entails more than ensuring that they get plenty of exercise and proper rest. He has adopted a new technology that is sort of an early warning system—a sensor which is worn in a small pocket under the horse’s saddle. The sensor uses GPS technology to measure the horse’s motion during training and racing, and Romans leapt at the opportunity to test the technology when his longtime friend Dr. David Lambert started talking about it.

“Dr. Lambert and I have been friends for a long time and he’s always doing some cutting-edge stuff trying to incorporate technology into this game, and so I always kind of follow what he’s doing.” Lambert is CEO of StrideSafe LLC, the company that introduced the sensor, which they call “the game-changer” for injuries to racehorses.

COVID to the Rescue?

Lambert has been using technology for years to monitor horses’ locomotion. “I used data collected at the breeze to predict racing talent,” he says. In 2018 he was a speaker at the International Conference on Equine Exercise Physiology in Australia, where he met David Hawke. “He had developed a very accurate and sophisticated sensor which had been used for timing and collecting biometric data for 10 years. He had 35,000 case histories taken from races!”

In 2019 Lambert’s company, Equine Analysis Systems merged with Hawke’s StrideMaster. Lambert began promoting the sensor to racetracks in the United States, where mounting injuries at racetracks were creating a groundswell of demand for changes to the industry.

Although he didn’t generate any interest, the landscape changed unexpectedly. “COVID came to the rescue, as my team and I were stuck at home,” he says. “We decided to spend that time reviewing all the data from all sources to see if we could recognize the stride patterns associated with catastrophic injury.” Success! “We began to introduce the idea at the track,” he says. “Emerald Downs (in Auburn, WA) was the first track in America to collect and study race day data.”

Today Churchill Downs requires every horse to be equipped with a StrideSafe sensor, and it has been that way since May. Even though Churchill Downs was shut down temporarily after the deaths of 12 horses, the sensors were required at their alternate racetrack, Ellis Park. Churchill Downs will reopen for the September and fall meets. The technology is also mandatory at several other racetracks across the U.S.

Lambert explains that the sensor is a GPS system that “measures forces generated by the horse and the way it runs. When something begins to go wrong, these forces change, and our sensors pick up those changes.” According to the StrideSafe website, the sensors collect data 2,400 times a second, and relay the data to computers. The data they collect on each individual horse create what Lambert calls the horse’s fingerprint. They know what’s normal for the horse, and the sensor can reveal even the slightest “abnormal” motion.

The initial presentation of data is in a “traffic light” format, indicating “Red alert: Major change from fingerprint, immediate scrutiny is indicated. Yellow alert: Small change from fingerprint, be on the lookout. Green alert: No change from fingerprint, no immediate concerns.” This is a critical warning system, as StrideSafe’s website explains that “it is known and widely published that in 85 per cent of catastrophic injury cases, necropsies had shown the presence of pre-existing pathology.”

Preventing Major Injuries

Trainer Dale Romans has been outspoken on the conflict between some in the racing industry and Horseracing Integrity and Safety Authority (HISA). He thinks, rather than fighting it, people should work together to make it better. He’s focused on horse safety and wishes more in the industry would do the same. “I think all these things can work together,” he says. “We can all work together on the safety initiatives and StrideSafe can be a big part of it. I don’t know whether it (StrideSafe) will ever be mandatory, but I think it could be a great tool. It’s sort of like when digital X-rays came around, or ultrasounds. You know, it’s another piece of the puzzle to try to keep these horses safe.”

Where StrideSafe is concerned, he’s a believer. “I can tell you there’s one horse of mine, I think we stopped a significant injury—or at least an injury that was going to keep him out of work for some time.” He says they didn’t see anything, but the sensor picked up something different, indicating potential trouble. “We sent him over and did a pet scan on his ankle and there was a very fine beginning of a crack in his cannon bone.” Romans says. “What we did was prevent a fatal problem, at minimum a six-month problem or a 60-day problem. I think David—I’m not speaking for him, but he really thinks that might be the very first horse he saved from having a major injury.”

The system doesn’t communicate with the rider, Romans explains. “What happens is the StrideSafe thing will come back and you look at the data and what we’re doing is we’re seeing the smallest changes or problems the horse is developing before the rider can feel it and before the trainer can see it.”

Because a horse can’t tell the trainers that he is in pain, or that his leg hurts, the sensors can speak for him—possibly even before the horse is aware of the pain. “In a perfect world, you could have a little light or something on the horse between the ears and the bridle,” Romans says, “and if the sensor felt the horse is off in the race or in the morning, the light would go on and the jockey would pull the horse up.” He says that option could warn the rider that there’s trouble ahead. It’s not a feature of StrideSafe now, but he thinks that someday it might be reality.

While Romans is looking to future technological breakthroughs, Lambert is focused on the here and now. “There is presently no ‘trouble ahead’ feature,” Lambert says. “The technology is there to provide such a feature but to introduce it would be complex. In my ideal world the industry would get behind this technology, stimulate and support the necessary research to move it forward and work closely with trainers and veterinarians to help them apply the findings to save horses. In the meantime, this is the course of action we will be following; watch this space!”